What happens to hounds from previous seasons?

By the start of the autumn a new hunting season is just weeks away, and with it will come cubbing. Huntsmen will train young hounds by having them chase and kill fox cubs. But what of hounds from the previous season? The ones that had begun to slow, or were showing signs of old age?

The hunt shoots them.

Darkest Secret

In October 2021, Protect the Wild published covert footage from the Duke of Beaufort Hunt’s kennels. It showed what the group described as “one of the darkest secrets of the hunting world”. The videos show men shooting multiple hounds before carrying them off for disposal in wheelbarrows.

In February 2022, renewable energy company Ecotricity published ‘Uncovered: Murdered hunt dogs powering our homes’. It contained undercover footage filmed at the kennels of the Carmathenshire Hunt. Its huntsman Will Pinkney is seen shooting hounds before throwing their bodies into bins. The Hunt Saboteurs Association later revealed the footage captured Pinkney shooting nine hounds in 40 minutes.

These two exposés are the first time that footage of hunts shooting their hounds has reached the public.

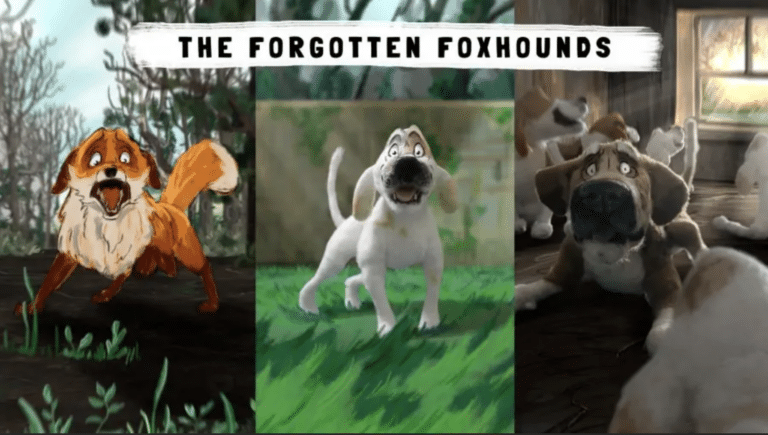

Protect the Wild’s ‘The Forgotten Foxhounds’ animation, narrated by Chris Packham and released in 2024, was based on these investigations. It has been viewed millions of times now and can be seen in full on our Animations page.

Numbering the Dead

Historical evidence of hunts shooting hounds has rarely made it to the public. In November 2020, Herefordshire Hunt Sabs posted a photo on Facebook of a dead North Herefordshire Hunt hound in a bin. And anti-hunting database Wildlife Guardian posted archival images of shot hounds belonging to the Cambridgeshire Hunt and Ludlow Hunt. But evidence and details of the practice had otherwise relied on writings by the hunts themselves.

During the Burns Inquiry, which ultimately led to the Hunting Act, the Countryside Alliance admitted that hunts would ‘remove’ 3000 foxhounds, or an average of 16 hounds per pack, before the 2000/01 hunting season. It also said that the number for other types of hunts would be proportionally similar. And that hunts would kill about 10% of this number of hound pups. Glen Black, writing for The Citro, previously calculated that this amounted to around 4,562 hounds and 600 pups killed before the 2000/01 season.

To establish how many hounds are killed, it’s first worth looking at how many hounds each hunt has. This will vary on the overall size of the hunt and how active it is. Anti-hunting group Protect Our Wild Animals (POWA) conducted its own research into figures generated by the hunting industry and took 29 couple (a couple is two dogs) as an average across the UK. Documents published by whistleblowing website Hunting Leaks also provide an idea of pack sizes. The Mendip Farmers Hunt meeting minutes stated the hunt had 40 couple but want to reduce down to 35 couple, while emails by members of the South Devon Hunt said the hunt had 44 couple of hounds at the start of the 2021/22 season.

On the other hand, the Countryside Alliance Burns Inquiry submission said there were 11,766 hounds across 185 fox hound packs, which provides an average of 63.6 hounds per hunt. This figure may be higher due to the age of the data or outlying hunts with exceptionally large packs.

Looking at how many are killed, POWA’s calculations suggested between 4942 and 7302 foxhounds killed per year across 195 packs, with approximately 3250 to 4500 of those in English and Welsh hunts. These approximate to 15% of hounds killed per pack. For one specific example, Hunting Leaks’s 2020 documents from the Mendip Farmers Hunt describe the hunt having killed 6.5 couple, or 13 hounds, between April and June of that year. This translates to roughly 16%.

So far as Protect the Wild can ascertain, there isn’t specific data on hunts in Scotland. However, the Countryside Alliance’s submission to the Burns Inquiry treated all hunts under the UK hunting associations as broadly similar in their approach, and these associations include hunts from Scotland. According to Baily’s, the hunting directory, there are 11 active hunts in Scotland. If we are to take the Countryside Alliance’s figure of an average 16 hounds and 1.6 pups removed per pack per season, that amounts to 193.6 hounds and pups in Scotland. That figure would be marginally higher using POWA’s calculations.

'Unfit’ for Hunting

Clifford Pellow, a former huntsman who became an anti-hunting advocate, provides a lower estimate. In ‘A Brush with Conscience – Why a Huntsman Abandoned His Sport’, Pellow wrote that “out of a pack of 60 animals, eight to ten are disposed of every season”. This is approximately 15% of hounds in a pack killed, similar to the Countryside Alliance’s own figures. Pellow provided insight into why hunts do this:

“Those [pups] that fail to make the grade get the bullet; they are taken round the back and shot.

“Dogs past their prime (generally, older than five or six years) are also killed.”

Hounds young and old are killed once the hunt believes they’ll no longer make for good hunting. It is also possible for healthy hounds to meet an early end if they’re seen as unfit for hunting. Writing about one of the shot hounds in its exposé, Protect the Wild said Scamp was a “playful” and “exuberant” hound. But this personality meant she did not function well as part of hunting pack. Meanwhile, Pellow wrote that ‘babbling’, or chasing after any creature, is reason enough for hunts to kill hounds, as is a hound that won’t ‘speak’, or notify the huntsman that it has found its quarry.

The Countryside Alliance’s submission to the Burns Inquiry also stated that:

“The hounds that are put down are those that are unable to keep up with the rest of the pack.

“No hunt can afford to keep any hound that is prone to “riot” (hunting non-target quarry). Some toleration can be afforded to young hounds in their first year of autumn hunting. Persistent offenders have to be put down, but in practice they are extremely rare.”

It is reasonable to assume this attitude applies to sick and injured hounds as well.

Wildlife Guardian’s article on the subject provides a graph illustrating the ages of hounds that are present in a pack. It chose three hunts from across England and Wales with figures sourced from POWA. The graph shows a notable drop off in hounds aged five or older. For comparison, the Kennel Club estimates the natural lifespan of a foxhound as “over 12 years”.

No Future

After our exposé of the Duke of Beaufort Hunt, the Hunting Office issued an internal memo that Hunting Leaks publicly published. It implied that the shot hounds were sickly, saying all hunts including the Beaufort Hunt take “appropriate health measures and preventative veterinary medicine” in the welfare of hounds. It also claimed that our footage was an attempt to “mislead the public”. Meanwhile, pro-hunting propaganda group This Is Hunting UK said “if a Hound is to be put down there must be a very good reason”. But Scamp shows this isn’t true.

This Is Hunting UK previously also claimed that hounds are “very often… returned to their walkers or live out retirement at the kennels”. And, as one example, it has posted photos of what it says is retired hounds of the Fitzwilliam Hunt. Meanwhile, an internal Association of Masters of Harriers and Beagles (AMHB) document lays out strict limits on re-homing hounds, including no re-homing through ‘third parties’.

There is no evidence backing up the claim that injured or otherwise unfit hounds are “very often” given the chance to live out their natural lives. In fact, the Countryside Alliance’s Burns Inquiry submission explicitly said that “there are very few instances of old hounds being re-homed on retirement”. The reason it gives is that hounds “will not settle” outside of the hunt kennel environment, although the AMHB’s document appears to contradict that statement.

Hunting's Isolationism

It would probably be inaccurate to say that hunts don’t care about hounds at all. Hunts put a lot of resources into raising and sustaining their packs, as suggested by the Hunting Office’s Kennel Management Course document. But it would also be wrong to say that hunts care about their hounds in the same way many people love their companion animals. Another document publishing by Hunting Leaks shows the South Devon Hunt describing the process of ‘reducing’ hound numbers in its pack as a “painful process”.

Hounds are, ultimately, a tool of the job for hunts. So it may be more accurate to say hunts care about their hounds in the same way that farmers care about their tractors or journalists care about their laptops.

In the end, the choice to not re-home hounds is an example of the hunting industry’s hallmark callous isolation. Shooting them when they are no longer useful for hunting, or only re-homing them to friendly landowners, is a choice to not invite outside participation in the industry. And the exposés by Protect the Wild and Ecotricity show the callousness with which this choice is carried out.

It’s worth finishing on a statement by Alastair Jackson, director of the Master of Fox Hounds Association (MFHA) when the Hunting Act came into force. What he says has been repeatedly claimed by sabs and monitors, and ultimately substantiated legally by the conviction of another MFHA chair, Mark Hankinson. In May 2005, just after the ban came into effect, Jackson told pro-hunting magazine Horse & Hound that:

“if the act is not repealed, the breed would disappear, because you need very few hounds to keep draghunting. If hounds were bred just to drag hunt or for show, they would alter drastically.”