Great Yarmouth magistrates found three people connected with the Dunston Harriers not guilty of illegal hunting.

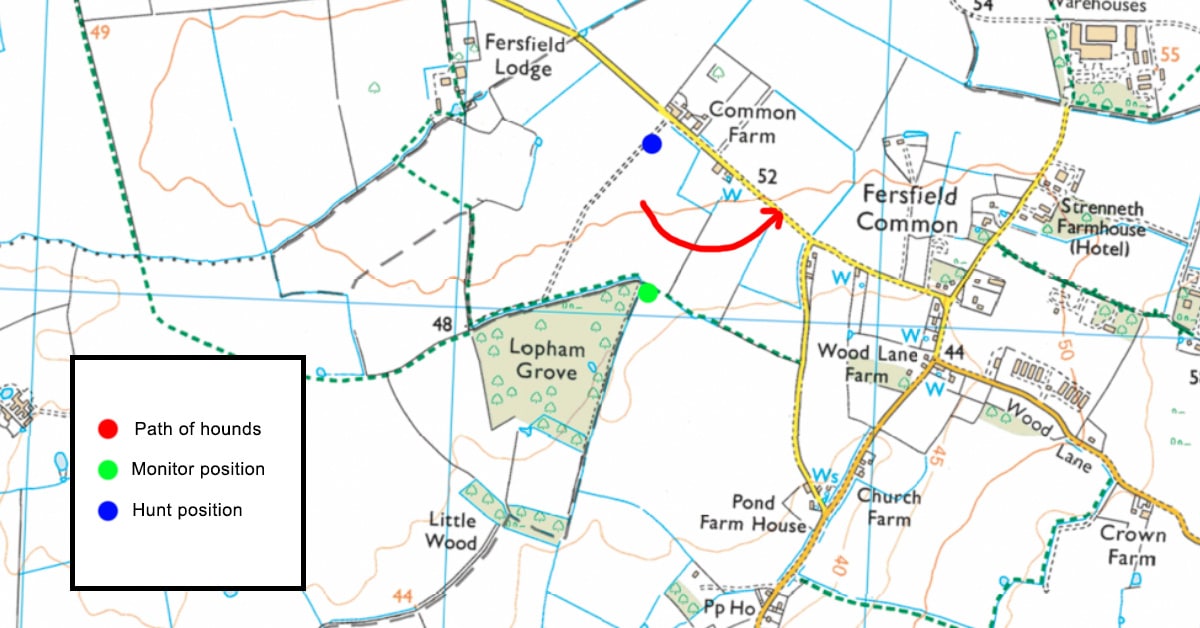

Geoffrey Block, Josh Worthing-Hayes and Lewis Ryland each faced a Section 1 charge of illegal hunting. The charges date back to 18 January 2022, when a hunt monitor from Norfolk and Suffolk Against Live Quarry Hunting filmed the Dunston Harriers’ hounds chasing a hare. The filmed chase took place in a field north of Lopham Grove in Fersfield, Norfolk.

The Hunting Act made hare hunting illegal, much as it did fox hunting. This included both hare coursing – conducted with sight hounds such as lurchers – and hare hunting, which is carried out by scenthounds including harriers, beagles and bassets. Harrier packs, unlike beagles and bassets, are mounted hunts and can at first appear very similar to foxhound packs. This is especially true of the Dunston Harriers. While most harrier packs traditionally distinguish themselves from foxhound packs by wearing a green jacket, the Dunston Harriers wear the same red jacket that the public is more familiar with.

Many harrier packs today hunt foxes instead of hares. The Dunston Harriers, however, are one of the few in Britain that continues to hunt hares as its primary quarry. Unless you believe the defence and Great Yarmouth magistrates, that is. The outcome largely reflected claims made by the defence, including that the Dunston Harriers was engaged in trail hunting. As a result, the magistrates ruled all three – two of whom are no longer part of the hunt – not guilty.

Following the verdict, Norfolk and Suffolk Against Live Quarry Hunting told Protect the Wild:

“Obviously we are disappointed with the verdict, but we knew, when magistrates accepted unsubstantiated evidence from those who were accused of what is essentially animal cruelty, that justice would be elusive. Nationally, the tide is turning against the hunting fraternity but here in Great Yarmouth, it is still flooding.

“Hasta la vista, Dunstons.”

The two videos filmed by Norfolk and Suffolk Against Live Quarry Hunting that were used as evidence against the Dunston Harriers in court.

The trial

The Crown Prosecution Service’s (CPS) case rested on pointing out that huntsman Worthington-Hayes and whipper-in Ryland didn’t do “all they could” to prevent the hounds from hunting. In particular, the CPS lawyer repeatedly returned to the fact that neither the huntsman nor whipper-in had attempted to call the hounds off as soon as they realised the pack was onto a hare.

Furthermore, after witnessing the hounds chasing a hare, they didn’t attempt to ride after the hounds, but instead waited and took a longer route around to where the hounds had gone after disappearing through a hedge. She also argued that laying a trail in an area with a “healthy hare population” meant that there was a greater likelihood hounds may get onto the scent of a hare.

In her closing statement, the CPS lawyer said Worthington-Hayes and Ryland:

“Did not use commands at the first instance to bring hounds back. [Master Geoffrey] Block said they would do everything they could, but it’s clear they didn’t do everything they could.”

The defence didn’t deny that hounds chased a hare. Instead, lawyer Stephen Welford focused on alleviating the culpability of the three men. This came down to three points (as extrapolated by Protect the Wild, not specifically laid out by Welford):

- Block had no involvement in controlling the hounds, and therefore was not culpable under a Section 1 charge.

- Martin Harrison and Minnie Rhodes had earlier laid a trail along the margin of the field that eventually saw the hare chase.

- Worthington-Hayes and Ryland didn’t chase after the hounds because the field was freshly drilled.

Points two and three were used to underline the need for the prosecution to show intent by Worthington-Hayes and Ryland, a frequent obstacle in Hunting Act cases. Welford summed this up in his closing statement, saying:

“It is not pursuit of a wild mammal with dogs that is hunting, but it is a person in pursuit of a wild mammal that is hunting.”

Before adding:

“Hunting requires specific intent. You’ve heard a specific acceptance that there is a risk a hare may be chased. That is recklessness – that is not what is required to convict someone under Section 1 of the Hunting Act.”

Ultimately, the defence’s case won out. Magistrates returned a not guilty verdict to all three charges, saying:

“Dogs are under the control of the huntsman and whipper-in, not anybody else, not the master.

“We believe Josh Worthington-Hayes and Lewis Ryland did everything they really could to bring the hounds under control. Chasing them over a field was not an option. Shouting or blowing a horn was not an option.

“The defendants attended the hunt to pursue trail hunting, which is a legal activity. There is no evidence to counter this.”

It’s worth noting that the magistrates’ summary largely reflected the assertions made in Welford’s closing statement.

What wasn’t asked

Given the defence argument was primarily based on the Dunston Harriers having laid a trail for the hounds, there was a surprising lack of evidence to prove the trail was laid. The CPS asked Worthington-Hayes what the scent was made from, to which he replied:

“I had a homebrew of shot fox that I soaked in water for about six months then strained off the fluid from that, and that’s what we used to hunt.”

Block stated that Harrison and Rhodes left approximately 15 minutes before the hunt in order to lay trails, and that a trail was laid along the margin of the field in which the hare was chased.

However, no evidence of the trail or trail laying was presented at any point. The assertions were accepted as fact, with Welford emphasising that none of the defendants had a previous conviction or caution against them and they were therefore entitled to good character direction. Trail hunting was, of course, specifically designed to exploit loopholes in the Hunting Act. And this case provided one example of how it is evoked as a smokescreen for illegal hunting.

The defence also made uninterrogated claims that the huntsman and whipper-in had acted “expeditiously” in attempting to call the hounds off. While the CPS did ask about using horn and voice commands, the defence was able to robustly shield itself against this by arguing that they’d have little effect once the hounds are in full pursuit of the hare. Instead, the huntsman said he and Ryland needed to “get to their heads” (in front of them) to stop them. This is broadly true when it comes to controlling hounds.

However, little was made of why the hunt would not already have positioned itself ahead of the hounds in case such an accident would happen, given that it knew the area had a “healthy hare population”. Instead, as the videos show, the hunt hung back some distance from the hounds. As a result, Welford was able to effectively argue that this was a case of recklessness and not intentional hunting.

Welford emphasised that the only experts on hunting in the case were the three defendants. Both the CPS lawyer and the magistrates appeared clueless about hunting. And the hunt monitor, though able to provide some details on the subject, wasn’t in a position to refute every argument.

And, ultimately, amongst all of the arguments by both the prosecution and the defence, there was one subject that disappeared completely: the hare. Few if any remarks were made about the creature, despite being at the centre of the entire case. Their fate beyond the chase is unknown.

Text book case for a new law

It is Protect the Wild’s perspective that this is a text book case for a wholesale replacement of the Hunting Act. While additions to existing legislation, such as a recklessness clause, could potentially have made the defence more difficult, it’s clear that the opaque subculture of hunting means any court case that depends on arguing technicalities in such complex legislation is destined to exploitation by the hunting industry. A lack of ‘expert witnesses’ to draw on in hunting cases reinforces the difficulties of successfully holding hunts to account through the courts.

As a result, there are only two things that will finish off the hunting industry: ongoing direct action, and a law that shuts down every hunt.

Watch Protect the Wild’s video about our campaign to end hunting permanently.