As the charity Butterfly Conservation(BC) puts it starkly on their website, “Following the results of the Big Butterfly Count 2024, Butterfly Conservation have declared a butterfly emergency, and we need your help more than ever before. By taking part in Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count – a UK wide survey, you can help assess the health of our environment simply by counting butterflies.”

The results from 2025’s ‘Big Count’ have just been released, and BC says that “while the numbers are a vast improvement on 2024’s record lows, experts warn urgent measures are still needed to reverse long-term decline.”

The charity goes on to say that “between July 18 and August 10, over 125,000 citizen scientists” (that’s you and me and everyone else who took part!) recorded 1.7 million butterflies and moths, with the top five species being Large White, Small White, Gatekeeper, Red Admiral and Meadow Brown.

Butterfly Conservation recognises a “marked improvement on last summer’s record low of just 7.2” individual butterflies per count, but notes that it is “only broadly average by modern standards”, and has done little to reverse longer-term declines.

Holly Blue, for example, had its second worst Big Butterfly Count result on record, Common Blue had its third worst and Meadow Brown had its fourth worst Count result.

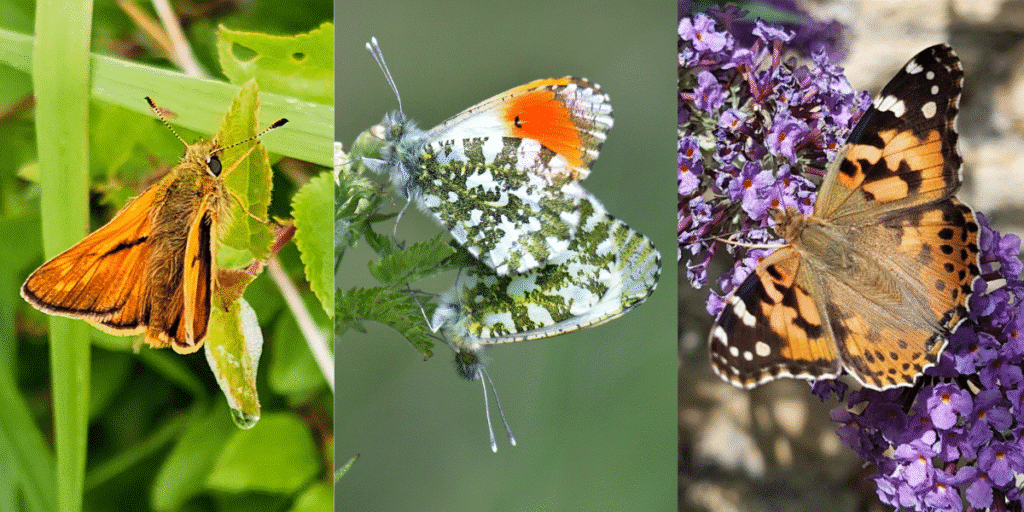

Orange-tip on Lady’s Smock

Butterfly populations in decline

I hope supporters will forgive a personal post on butterflies and the Big Count, but I’ve been fascinated by butterflies for many years. I am fortunate to live in rural Wiltshire, and over the last fifteen years or so have recorded almost half of the UK’s 60 or so butterflies in our garden (including a single White Admiral, several Silver-washed Fritillaries, one or two Clouded Yellows, and good numbers of my personal favourite, the Orange-tip).

I have taken part in the Big Butterfly Count since it was launched in 2010, and last year was indeed awful. My own experiences reflected what the 2024 Big Count found across the country: once abundant Small Tortoiseshells had disappeared (a 2023 article in The Guardian noted the species had declined by 82% across the UK since 1976), Common Blues had declined markedly (the species is in long-term decline in the UK due to habitat loss caused by agricultural intensification and the destruction of traditional grasslands), and butterfly numbers were generally a fraction of what I normally expected to see.

2025 has seen some small changes in the butterflies on ‘our patch’, and they again mirror the broader ‘Big Count’ findings. Large and Small Whites (and in our case, Green-veined White as well) have been very numerous. Peacocks were everywhere in the Spring, and Small Coppers seem to be having a third generation this autumn. Walking locally, I found Meadow Browns in huge numbers on a ‘set aside’ close by to our house. A Marsh Fritillary in May less than a km from the house was a local ‘first’ and (the county recorder postulated) a wanderer in hot weather from chalk grassland halfway across the county.

Silver-washed Fritillary on buddleia

A ‘first for the patch’ is always exciting, but far more important are the numbers as a whole. I’ve seen almost no skippers this summer, no Small Heath, just one or two Ringlet, and just a handful of Small Tortoiseshell all year. Moths are down too. We’ve lost Ashy Mining-bees and Rufous Mining-bees from our lawn (and most of the bee-flies that utilise them), seen a fraction of the hoverflies we’d normally see, and seen far fewer earwigs. For the first time in years there was no “Flying Ant Day”, when the Black Ants under our garden would typically emerge in clouds and spiral off to find new areas to nest.

We’ve not changed how we garden. We leave patches of grass unmown all year, we’ve never used pesticides, and we plant specifically for pollinators. We’re of course not immune to the massive changes taking place on neighbouring farmland and the climate as a whole, though. Perhaps some of the very local changes at home are down to a very wet spring in 2024 being followed by an early 2025 which baked the ground hard.

Peacock on bullace blossom.

Shifting baselines

In February 2023, Butterfly Conservation released “The State of the UK’s Butterflies 2022’ Report, which stated that 80% of butterflies in the UK “have declined since the 1970s”. That translates to, on average, UK butterflies losing 6% of their total abundance at monitored sites and 42% of their distribution between 1976 and 2019.

Butterfly Conservation describes a scenario where “those born in 1976 will only be in their 40s now, and yet in their lifetime more than three quarters of our butterfly species have declined in abundance or distribution”. That probably includes many of the supporters reading this post.

They use a 1970s baseline and 1976 in particular, because that’s the year that proper butterfly monitoring in the UK began with the establishment of the United Kingdom Butterfly Monitoring Scheme (UKBMS). Which is important to note in relation to the phrase they use in their report on the 2025 Big Count: “only broadly average by modern standards”.

We are all susceptible to thinking of things in terms of ‘shifting baselines’, where each new generation accepts a degraded state as normal or typical because that is what our own experience tells us. By the 1970s the UK had already seen a “second agricultural revolution” and the loss of vast areas of flowering meadows so important to butterflies and other insects. We’ve lost over 97% of these habitats since the 1930s, a huge chunk of them between the 1950s and 1980s before monitoring on a national scale began. The ‘broadly average’ numbers of today are little more than the diminished remnants of vast butterfly populations that existed just before World War II, and even they were almost certainly down on the abundance that the Victorian butterfly collectors would have recorded.

As Patrick Barkham put it so well in 2009,

“Near contemporaries of Rothschild wrote of skimming hundreds of purple hairstreaks from the trees or catching 100 Lulworth skippers in an hour. In 1892, SG Castle Russell took a walk through the New Forest: “Butterflies alarmed by my approach arose in immense numbers to take refuge in the trees above. They were so thick that I could hardly see ahead and indeed resembled a fall of brown leaves.” A few centuries earlier, Richard Turpyn recorded a probable mass migration to or from Britain in his Chronicles of Calais during the reigns of Henry VII and VIII: “an innumerable swarme of whit buttarflyes … so thicke as flakes of snowe” that they blotted out views of Calais for workers in fields beyond the town.”

Yes, I was excited to see my first Marsh Fritillary here, but set alongside the loss of millions of butterflies…

Brimstone

Why Counts Matter

Whether I see fewer butterflies or not is hardly the point, of course. What matters is what it means to the environment and to the wildlife that all of us here at Protect the Wild care so much about. Butterflies are an excellent indicator species, and if they are suffering then countless thousands of less well monitored species will be suffering too. And invertebrates, as the charity Buglife cheerfully labels them, are the ‘small things that run the planet’. They pollinate, they recycle plant matter, and they are feasted on by everything from birds and bats to small terrestrial mammals, fish, amphibians, and other insects.

We need to know what is happening to them, so that we can do something about it.

It can be uncomfortable. We all know that. Most activists (and we are all activists at Protect the Wild) feel overwhelmed sometimes, but while no one actively wants to feel that ‘it’s all too much’, it is vital to recognise that part of the reason we feel this way is because we all know far more about the state of the world than ever before. And we know, because researchers and the public alike have collected masses and masses of data. Like Big Butterfly Counts and the RSPB’s Big Garden Birdwatch.

So, will I be back counting next year, then? Absolutely I will. It’s fun, it’s educational (I didn’t always know my Wall Browns from my Gatekeepers), and it’s easy. And it’s an excuse to get up from the laptop and wander about outside. I can recommend that last reason very highly indeed!

Do I fret about fewer butterflies knowing that with the best will in the world I can’t change the weather? Of course. But I can campaign against pesticides, work to persuade family and friends to go beyond ‘No Mow May’ and leave a bit of the garden permanently wild, and put water out for wildlife when it’s too hot. I can go out and count and send my data in. I can contribute in a myriad of ways. And back in the Protect the Wild world, I can also work to end hunting with hounds, the badger cull, and of course end bird shooting.

Are any of us changing anything? It will never be as much as we’d like, but always far more than if we did nothing at all. And, really, that alone is enough to keep me going…

- All photos Charlie Moores